Enterprise Architecture Archaeology

When I turned 50, I asked some of my girlfriends, all actresses of the same age, 'What are we going to do now?' I wanted to go live somewhere for a while, learn archaeology, or take part in healing the world on some level. I wanted to dig deep ...

- Goldie Hawn

Fig 0: The Age of Information / Age of Computing

History Catches Up!

The Age of Computing was helped significantly by industrial certifications and attempts for standardization. This worked, but left a diverging and growing gap between legacy core systems on older technologies with newer frameworks and their dependencies.

Most enterprises have a strong veneer of modernity, but in my experience are underpinned by massive sets of decades old mainframes, proprietary entrenched systems, and generally lost tribal knowledge.

While technology is certainly always pushing the boundaries and moving at an incredible pace, the timeline is expanding. In many cases, the original authors and engineers of the systems have since retired, moved on, and due to the timelines with the Age of Computing/Information, some are unfortunately deceased. The timeline of the Age of Information marches on.

So how do we take stock in the past, and build on the great work already done? In my experience, a good percentage of previous engagements have leaned heavily on ‘Architecture Archaeology’. Afterall, like Maya Angelou said “You can’t really know where you are going until you know where you have been.”

Fig 1: An architect descends into a new LOB (Line of Business) to find the treasures of ‘current state’

A recent example of this would be as a lead architect and consultant for a very large M&A (Merger and Acquisition), subsuming a new external line of business into the enterprise. This SAFe AGILE program consisted of over 30 AGILE ‘trains’ associated with particular capability areas or system alignment; from claims analysis systems, to video and voice communications, mainframes to open-source Netflix OSS applications. While several architects were involved in individual trains, it was my duty to guide and weave this massive multi-billion dollar business into an existing centuries-old enterprise; in a period of less than a year.

The end result was ‘indispensable’ to the enterprise. The work itself required a significant amount of ‘digging’.

Fig 2: An ‘Architect Archaeologist’ approaches a forgotten system.

Through a myriad of interviews, workshops, and generally piecing together the puzzle of two giant companies; I was able to create train specific solution architecture artifacts that guided each application into the port of delivery, captured risks and assumptions; and created large ecosystem plotter diagrams with 100s of systems, their dependencies, and technological profiles. These artifacts were used live in every PI (Program Increment) event as well as referred to and groomed in countless workshops. This could not have been done without some modicum of ‘Enterprise Architectural Archaeology’.

Archaeology Practice

“The science and practice of Archaeology is the is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture.“

In this case the analysis is being done by the architect or set of architects and analysts, and the material culture are the IT assets and associated processes of established capabilities.

Quick Shoutout: ‘Human Activity’ was bolded for a reason, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t shout-out “Wittij People Centric Architecture”, which was added to OpenGroups recognized methods in 2022.

But how do we get to the evidence? In archaeology there are several types of digs or excavation, the two most common are:

Fig 4: The human element is always present, and should never be ignored.

Research excavation – When time and resources are available to excavate the site fully and at a leisurely pace. These are now almost exclusively the preserve of academics or private societies who can muster enough labour and funds. The size of the excavation can also be decided by the director as it goes on.

This is very much akin to funded ‘Discovery’ work at institutions and enterprises.

Development-led excavation – Undertaken by professional archaeologists when the site is threatened by building development. This is normally funded by the developer, meaning that time pressure is present, as well as its being focused only on areas to be affected by building. The workforce involved is generally more skilled, however, and pre-development excavations also provide a comprehensive record of the areas investigated. Rescue archaeology is sometimes thought of as a separate type of excavation but in practice tends to be a similar form of development-led practice. Various new forms of excavation terminology have appeared in recent years such as Strip map and sample some of which have been criticized within the profession as jargon created to cover up for falling standards of practice.

This is a more common scenario for an enterprise or institution, usually driven by a business-case with achievable ROIs (Return on Investments) or positive CBAs (Cost Benefit Analyses)

Fig 5: An archaeologists toolkit, note that half of this kit is informational/data centric such as the notebook, leveler, and twine.

The primary method in which excavation occurs is through Stratigraphic Excavation, or peeling back the layers in time from the present and recording through the layers.

How do you go about retrieving and cataloguing the archaeologically significant finds? A couple methods remain the primary means of excavation:

Flotation: Separating the sediment from the smaller artifacts through flotation and water.

This isn’t the ideal scenario in IT, but it is a method that is used. Transforming known critical systems, those components that survive float to the top, and some are forgotten or retired. Think MVP.

Sieving: Sieving the dirt to find the significant items.

Our preferred method if time and money allow. We work through the strata, from business architecture down to the infrastructure. A more measured approach.

Every great anthropologic and paleontologic discovery fits into its proper place, enabling us gradually to fill out, one after another, the great branching lines of human ascent and to connect with the branches definite phases of industry and art. This gives us a double means of interpretation, archaeological and anatomical. While many branches and links in the chain remain to be discovered, we are now in a position to predict with great confidence not only what the various branches will be like but where they are most like to be found.

- Paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, 1925

Henry Osborn said a lot there, and is speaking to confident assumptions based on evidence; something architects rely on. The correlation between archaeology excavations and systems portfolio analysis are many. Often architects and IT leaders are asked to identify the ‘current state’ to prepare for transformation, and in many of these cases these groups owning the applications or systems are not the same people that built and maintained them. This event, or exercise, is similar to the archaeologists excavation, carefully peeling back the layers of strata to reveal the links in the chain, and the value therein.

Common Approach

The common approach to discovering and unveiling the current state is similar to archaelogist’s first step: Research!

Fig 6: An architects sifts through an enterprise repository.

Prior to a dig or during, an archaeologist will have studied available material pertaining to the dig; in some cases, years of academic study. In the case of the ‘architect archaeologist’, this is akin to accessing documentation repositories, and in some cases these are documents decades old. This gives us an iota of information on ‘evidence’, the things that we know or assume to know and have record of.

After cramming what is known from previous research and material, we need to start digging. Now this is where we start to diverge from the archaeologist, in that we have inhabitants of this land still around to talk to; these are the IT owners, the SMEs (Subject Matter Experts), the DBAs (Database Administrators); e.g. the people doing the day to day operational work and executing new ideas. But before we talk with them, let’s dig a little or at least check our own records…

Archaeology is the search for fact, not truth ... We do not follow maps to buried treasure, and 'X' never, ever marks the spot. Seventy percent of all archaeology is done in the library. Research. Reading.

- Indiana Jones

The Dig

Fig 7: Typical EA stack of domain knowledge (TOGAF9)

Like Dr. Jones said, preparatory knowledge is required. Enterprise Architecture, and it’s associated sub-domain practices (Business, Data, Application, Technology/Infra, Security) are a holistic practice and mastery of all domains of architecture and computing. More importantly, it weaves this mastery into cultural understanding, and scientific processes of analysis (e.g. SEI ATAM). This statement is key, as a holistic understanding will be necessary to navigate the complexities and myriad of roles in the dig, interviews, and workshops to present and identify findings.

The manual digging and excavation requires access to information; in most enterprise or corporate environments there are a myriad of measuring tools and metrics to report on.

Examples of available dig sites can include:

Fig 8: Some EA (Enterprise Architecture) can contain over 20,000+ artifacts/documents.

CMDB (Configuration Management Database): This contains the configurations, dependencies, and deployment information. And in many cases have discovery agents, that will automatically search out and display dependent information.

Architecture Repository: Most corporate environments will have vast design and documentation repositories. And although this data may seem outdated, it usually is spot on. Bonus points to discern the past repository model with the change management log in CMDB!

IT Finances: A telling way to understand the depth and size of the current ecosystems, oftentimes seperated by CapEx (Capital Expenditure, e.g. Build/Improve) and OpEx (Operational Expenditure, e.g. keeping the lights on). By extrapolating these costs by blended rates, one can get a good idea for the manual intervention required, or the average run rate to keep the system operational. Distinction between CapEx and OpEx records can identify when changes occurred if attempted.

Configuration Tickets: A great amount of effort lately has been put into IT self-service as well as self-provisioning tickets in enterprise IT. If this data is available, in a platform such as ServiceNow or similar, it can provide clear timelines into functional and relevant changes. This data can be used to updated older findings or records into a more coherent and relevant current state.

Process Analysis/SIPOCS: If available, any dated process analysis will be useful, as process and flow are design components for the solution at hand. Understanding the base requirements in relation to the organization and culture is key at formulating a finding or recommendation.

Compliance Evidence: This is a trending topic, but technology companies are constantly striving towards measurable certifications for the marketplace. Traditionally compliance has focused on financial audits; but what we’re talking about here is certification compliance: The ISO numbers, PCI for payment, CStar for security, etc. If a company is expanding their marketplace footprint through industry certifications, then the evidence has been collated and is available through the diligent work in compliance.

Now, when an archaeologist finds an artifact, they don’t just file away it away with a tag and call it a day; and neither will we.

Evidence and Status Logging

We need to create our own models, spreadsheets, or data dashboards to facilitate our findings and provide ways of correlation and communication. So we will use a few basic templates:

Fig 9: Digging the infinite mines of architecture repos.

System Catalog: This usually contains several columns of pertinent information dependent on the proposed vision, e.g. if this is a cloud migration, the 6 R’s may be prevalent as status options. If this is a data-heavy processing suite, identifying the base-line databases will unveil their own native constraints and may facilitate ETL. The list goes on, but make this catalog pertinent to the vision at hand, and the overall ask. Don’t record EVERYTHING, referencing back to your sources is sufficient. Continue to evolve this as the source of record for systems. There will artifacts such as Logical Designs or TRDs (Technical Requirement Design) that will contain the details at a later time.

Models and Views: Start modeling and viewing immediately, this will not only keep things fresh, but exemplify the sequence of understanding and analysis, and will be very useful in the next steps. Bonus points if you use data-driven data visualizations directly off the systems catalog.

Interviews

Lets put away the shovel for now as we start identifying the people that own and run the systems pertaining to our dig. These interviews are done quickly, with preparatory models to be used to facilitate the interview, in most cases these are Conceptual Models or rough Logical Designs based on previous findings and new assumptions.

These interviews are done in two phases, the first being the initial discovery conversation to outline the overall approach and provide context to the interviewees. The second interview will involve validation of the solution at hand, from the people that lived and worked it; more akin to anthropology or sociology.

Workshops

We conduct these interviews in workshops, 30~ minute conversations with a set agenda and expected outcome. In some cases, we will build and refine models during the workshops; but ideally we show up with assumptions in hand and present.

Publish Findings

Fig 10: Forgotten mainframes

Like any good archaeologist, our goal is to publish our findings!

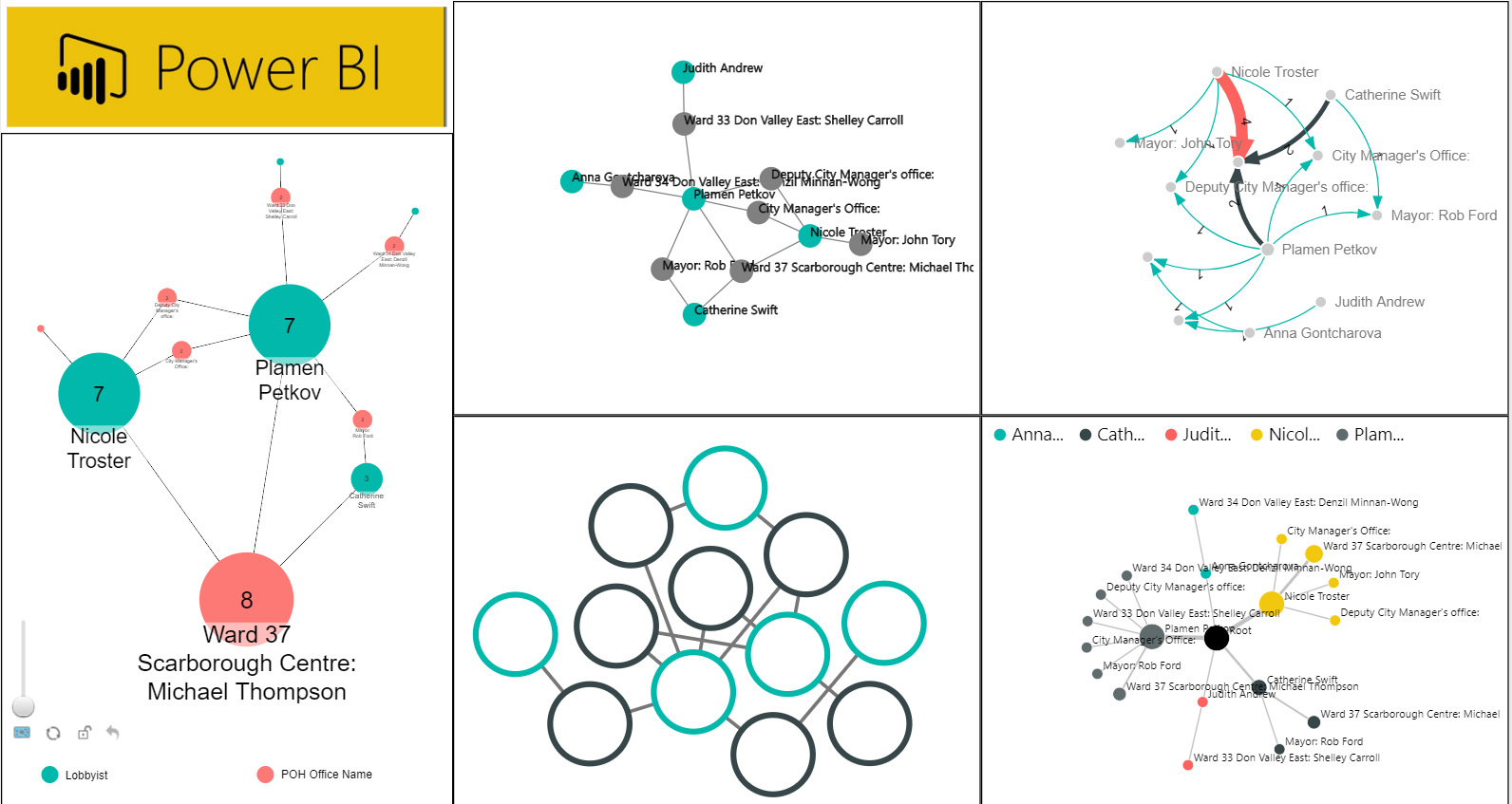

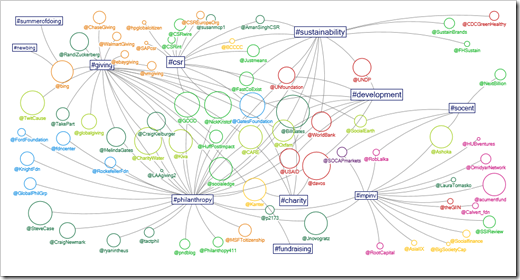

This is always indicative of the culture of the organization. In many cases these findings are synonymous with our Evidence and Status Logging. These artifacts we created, can be leveraged in a myriad of ways to create clear findings. In the past I’ve used visual dashboards such as Tableau or PowerBI, in some cases these presentation materials may need to be groomed via data visualization practices.

Examples below are node link diagrams on two popular BI (Business Intelligence) platforms:

Fig 11: PowerBI

Fig 12: Tableau

Publish Recommendations

Fig 13: An Architect Archaeologist attempts to replace a component.

Findings and recommendations are two very different deliverables; one is factual based on our dig evidence and data, and the other is a calculated vision with additional strategic context, akin to a roadmap.

Often, EA findings will not be enough, as the leadership of the institution will look to the architects to design the future as thought leaders.

How you publish your recommendations are usually tied to the scope of your engagement as an architect. Leveraging and presenting the great work already done and identifying clear risks, can provide confidence in your organization and lead to a pragmatic and achievable target state recommendation. The modus of this, is most commonly a slideshow presentation (PowerPoint, Slides, etc.), where highlights can be presented over a backdrop of established evidence from all that digging.

The parallels are there, and although we as architects and IT leaders sift through the strata of information; it is oftentimes clear as mud. Somebody has to get their hands dirty to discover the facts. If not the architects, then who?

If an ancient city survives to become a modern city, like Naples, its readability in archaeological terms is enormously reduced. It’s a paradox of archaeology: you read the past best in its moments of trauma.

- Professor of Roman Antiquities at Cambridge University, Andrew Wallace-Hadrill